Ingolstadt - Artist’s Statement

The making of a monster game

12 Jun 2024

Play Ingolstadt here!

Ingolstadt was initially conceived as something like a challenge: how would one make a video game adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein? Would it even be possible? How “faithful” could you remain to the original plot? At first, I imagined that there must be some way to convey the experience of Victor Frankenstein as he assembles and subsequently flees from his creation. If we consider problem-solving to be the main driving mechanism behind video games—as adaptation theorist Linda Hutcheon suggests—to adapt a story like Frankenstein might be to transpose Victor’s problems (making an animated body, enduring the horror of that body) onto the player. However, in thinking more about the project—and considering restraints like time and skill—I ended up making a game wherein the player takes on Frankenstein’s monster’s problems, specifically his existential problems. Much of my inspiration came from Susan Stryker’s essay “My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix,” in which she likens the experience of being a transgender (and self-identified “transsexual”) woman to the experiences of the Creature from Shelley’s novel.

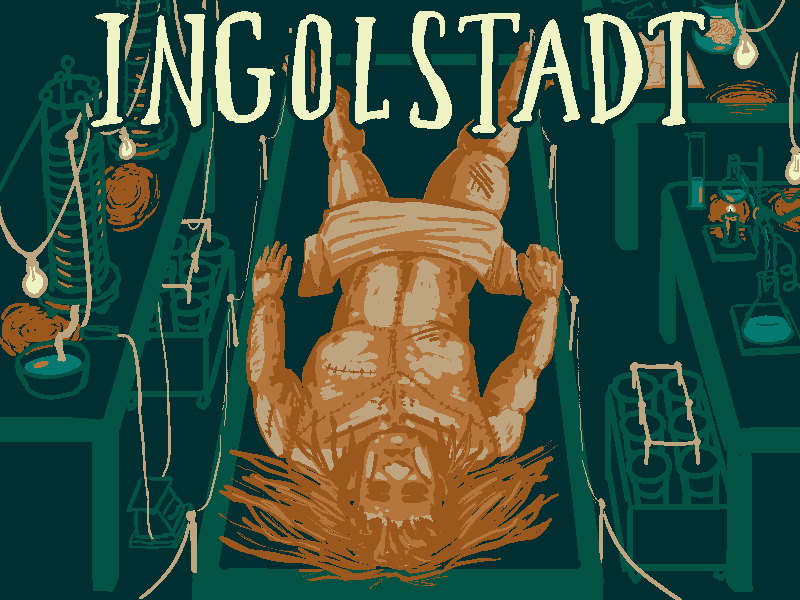

Ingolstadt is named for the site of the Creature’s creation in Frankenstein, something that grounds the game in the world of the novel. (I was also subconsciously inspired by the titling of the game Elsinore, a re-interpretation of Hamlet.) The scenery is likewise inspired by the particular historical setting of the novel: the Creature lays on a table surrounded by Leyden jars and other early electrical technology. Having that sense of place, however small, felt important. Though Ingolstadt doesn’t much follow the plot of Frankenstein, I wanted to suggest that it takes place in that universe, and that the facts of the world as seen in the novel (that the Creature is seen as a monster, that his creation must involve animation from dead tissue) hold true.

To create the body parts of the Creature, I had a few guiding principles. First, I wanted them to be gross and dead-looking. This informed the color scheme, which is close to the novel’s description of “yellow skin,” and the various scars, scratch marks, pockmarks, and otherwise rough coloring. For Victor Frankenstein, part of what makes the Creature uniquely horrific is the way that his “muscles and joints were rendered capable of motion.” I haven’t done much animation before, so rather than making the contrast between stillness and motion the cause of the horror, I instead tried to contrast the clean, simple lineart of the part-selecting UI with the more “ugly” looking body parts. For example, the “face” button has clear eyes, whereas the monster’s potential faces don’t. This was supposed to represent Victor’s project of making the Creature especially beautiful: I gave the UI body parts conventionally attractive masculine features, such as muscles. While I tried to represent a somewhat diverse range of faces and body types for the various parts, I also consciously skewed masculine, choosing to, for example, look at pictures of cis men rather than women as references for drawing musculature. At the same time, I also added some features typically thought of as “feminine,” such as breasts.

Something that helped me crystalize a lot of my thoughts on how I was portraying gender in the project was the aforementioned Susan Stryker essay. In this essay, Stryker explains how her own experiences parallel those of Frankenstein’s monster. At the core of this comparison is her understanding of the transsexual body (that is, the body of a transgender person who is, in some way, in the process of medical transition) as an “unnatural body”: “flesh torn apart and sewn together again in a shape other than that in which it was born.” Like Frankenstein’s monster, she explains that she is “too often perceived as less than fully human due to the means of [her] embodiment.” She also makes comparison between Victor Frankenstein’s purpose of mastery over nature and the culturally conservative “scientific discourse that produced sex reassignment techniques,” which she argues “is inseparable from [...] the fantasy of total mastery through the transcendence of an absolute limit, and the hubristic desire to create life itself.” Like Frankenstein’s Creature, however, transgender people have taken these so-called unnatural scientific origins and redefined themselves as “something other than the creatures our makers intended us to be.” Just as Victor Frankenstein cannot control his Creature or that Creature’s feelings, those who created sexual reassignment surgery as an “attempt to stabilize gendered identity in service of the naturalized heterosexual order” cannot control how transgender people define themselves. In my game, I try to merge these two ideas by asking the player-as-creature to name themself, literally deleting and overwriting phrases that Victor calls his Creature in the book (“miserable monster,” “filthy daemon,” etc).

Stryker finds empowerment in this embrace of monstrosity and unnatural construction. She suggests that accepting herself as a “creature,” a “created being,” is an acknowledgement of her “egalitarian relationship with non-human material Being,” and that other, non-transgender individuals—especially those who feel threatened by the category crisis that trans people represent—should similarly “investigate [their] nature” as a constructed being rather than a “natural” one. These were the ideas that I was trying to represent with the questions at the end of the character creator. Though answering “yes” or “no” doesn’t change anything in the game, posing these as questions invites the player to stop and reflect. One question addresses the player-slash-creature as a being “constructed against the natural order;” another asks them to make peace with their perceived monstrosity, something that Stryker has certainly done. The last question asks the player if they agree that everyone is “formed from things other people made up.” This is my nod at the culturally-constructed nature of gender and identity. I also hope that the variety of unusual options in the character creator, such as the option to make the Creature’s limbs asymmetrical, fosters in players a sort of glee in becoming more monstrous or incongruent.

Stryker understands Frankenstein’s monster as “his own dark, romantic double, the alien Other he constructs and upon which he projects all he cannot accept in himself.” Though character creator games are certainly not only meant for creating representations of oneself, this is how they are commonly used: on Picrew, for example, creators often encourage the player to make either a realistic or idealistic version of themself by including lots of facial customization options that correspond to real-world features. I purposefully denied the player the ability to make a Creature who looks exactly like themself, both thanks to the undead-ness of the Creature and the relative lack of customization options. I also injected a bit of Victor back into the project with the randomly-appearing commentary attached to various body parts, which anonymously muses not only about the technical or medical aspects of creating the Creature, but also hints at how those body parts may be socially construed. This creates the feeling of a creator reflecting on a creation, though this creator is purposefully ambiguously located and debatably real. At the same time, I refer to the player as if they are the Creature: naming the Creature, for example, comes along with the prompt “My name is,” encouraging the player to identify themself with their strange creation. Though players are taking the place that Victor takes in the novel, the genre of the character creator creates an ambiguity between creator and creation that I find interesting in terms of transgender experience.